He Came

He came! Into the humblest birth

He came! A god to walk on earth

He came! To conquer death and sin

He came! And He will come again.

He Came

He came! Into the humblest birth

He came! A god to walk on earth

He came! To conquer death and sin

He came! And He will come again.

Dear God,

I’ll admit: I didn’t see this one coming. It wasn’t that I didn’t think I would have serious trials again. But I wasn’t expecting to be in harm’s way again while I was still recovering from the last go-round. Little faster than I would have anticipated. And a lot more intense. But here I am on Christmas morning, one that I had no business seeing, pondering my inventory of afflictions and blessings.

The afflictions are easy to count. Since this time last year, I’ve had antibiotic-resistant pneumonia, in both lungs. The pancreatitis took my major organs off line. Did that dying thing. The monster cyst. That crazy nose bleed during the summer (blood coming out of my eye sockets was a nice touch, by the way). The operation that went wrong. The aneurysm. My numb leg. 11 scars on my torso. Numerous scars on my hands and arms from all of the IVs. Considerably less hair than I started the year with, and a greater portion of it grey.

Yeah, I’ve aged about a decade this year. Been rode hard, and I see it when I look in the mirror. I feel it, but only when I move, sit, or lay down.

The blessings? Those are harder to count. They always are. While afflictions pout, yell and gesticulate for attention like a petulant three-year old, blessings have a way of creeping up next to you quietly, doing little if anything to announce their presence. You have to look to find them, and who wants to go to all of that work when you have the bratty problems of your life right in front of you?

But I have learned that the blessings are there. I’ve written about several of them over the last twelve days. So much for which I have to be grateful. But one blessing I’ve said little about, and it’s one of the greatest that you have given me this year. It was a message hidden behind all of these other blessings, one that I needed to hear, and that I have paid so little attention to over the years. It was a simple, whispered assurance of a truth that I have rarely believed:

I matter.

I have felt more than a little like Ebenezer Scrooge as I have gone through this process of fading and recovering. I have had the opportunity to be reminded of some of the good things I have done in the past that have helped other people, and I have been given a glimpse of how things would be without me. I have seen that despite all of my faults and failures–and they are legion–the blessing of life has not been completely wasted on me. I’ve been able to do enough with my life that I would be missed if I were gone.

I have not always felt that way. There have been a few times in my life when depression has taken me down dark paths that could have led to scary results. I felt more than once that few would mourn my passing, and that some might be better off as a result of it. The scariest of those demons were slain some time ago, but I still question my relevance.

You showed me something different this year. I’ve seen, or at least heard of, the scores of people who visited me or my family in the hospital, who stood at the wall with my wife, and who prayed for my survival and welfare. I’ve had people offer help because, according to them, they felt some sort of obligation to me or my family as a result of mostly forgotten small acts of service that we had done for them. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not saying we deserved the kind of help that we received. No one does. But the things said by those giving us help reminded me that I along the line I had done enough to bind me with people in the way that only service can bind you together. You have showed me that little things add up, and that we all need each other. Every little act of service given to me has made a difference and has irrevocably changed how I see the people who offered them. If their service makes a difference, then so can mine. I’ve mattered to good people. I’ve sometimes been a helper.

On top of that, I have seen the genuine and heartfelt relief expressed by friends (old and new) when they find out that I was able to cheat death and find a path to recovery. I cannot and will not doubt the sincerity of those expressions. More than ever before, I had an appreciation that if I weren’t here, that loss would be felt by others. It imposes on me an obligation to validate their expressions of relief by ensuring that my preservation serves a purpose. I matter, and I need to make sure that I find ways to continue to matter.

Then you gave me the final assurance of my value: You saved me. I have no idea why I have been preserved through multiple threats to my survival. I am clueless as to why so many people, including countless people who are much better than me and make a bigger difference than I ever have, are taken back to you under less severe circumstances. I cannot pretend to explain why you have performed one miracle after another to keep me here. I just know that you have. For whatever reason, I was worth the rescue, several times over. I matter to you.

Thank you for that repeated whispered message. And thank you for the message that echoes behind it:

We all matter.

Everyone is worth a rescue. Everyone is worth the effort of service. Everyone means something to you, and therefore should mean something to me. If the likes is worth a miracle, then everyone is. This journey of life is a struggle, sometimes a mighty one. Understanding that we matter, that everyone matters, means that it is always worth stopping to offer a kind word, a lifting hand, or a supportive shoulder. We need to believe and have faith that our little contributions make a difference, that our feeble strength can be magnified through your grace in such a manner that it moves people in lasting ways. We need to remember that we matter, and we should cultivate sufficient compassion that everyone matters to us.

Thank you, God, for the miracles. Thank you for the rescue. Thank you for the reminder.

Over the last several days, I have written about the past nine months of my medical issues as if it were my story. In truth, I own very little of this story. For large parts of it–indeed, for the worst parts of it–I was either unconscious or not fully aware of what was going on around me. I did not have to bear the burdens of making potentially life-altering medical decisions, informing friends and family of my condition, watching the progression of my condition, feeling the hope of recovery squashed by another reversal. I didn’t have to worry, because I didn’t know I was supposed to.

I wasn’t the one who prayed that if her spouse was going to die, it would happen quickly.

All of those burdens, the heaviest and hardest loads, rested on my remarkable wife.

There is absolutely no way that a blog post adequately can express the depth of my debt to Esther, nor would it be  appropriate for me to express here the degree to which I love her. 2015 has been a horror story for her. Not only did she have to support me during my ordeal, but at the same time her father was in hospice care, working out the final weeks of his time on earth. The shadow of death has hovered over Esther almost without interruption this year, which is more than anyone should have to experience. By the end of the year, her own health would suffer, and she would have to have surgery for a painful sinus condition. Throw on top of that financial worries, concerns about the security of her job, and family issues that tugged at her heart. I am sure that if she could have selective amnesia, she would throw 2015 on the ash heap of the forgotten.

appropriate for me to express here the degree to which I love her. 2015 has been a horror story for her. Not only did she have to support me during my ordeal, but at the same time her father was in hospice care, working out the final weeks of his time on earth. The shadow of death has hovered over Esther almost without interruption this year, which is more than anyone should have to experience. By the end of the year, her own health would suffer, and she would have to have surgery for a painful sinus condition. Throw on top of that financial worries, concerns about the security of her job, and family issues that tugged at her heart. I am sure that if she could have selective amnesia, she would throw 2015 on the ash heap of the forgotten.

![unnamed[4]](https://mutteringmormon.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/unnamed4.jpg?w=225&h=300) While I slept, she fought. She fought for me to get proper treatment. She fought to stay by my side, knowing that my fear of hospitals and my claustrophobia would lead to a panic attack when I woke up intubated and tied to my bed. She fought for a private room, because it would be the only way that she could stay with me. She fought exhaustion and worry. She fought fear. She fought a dozen enemies, any one of which I probably would have run from. Ultimately, however, the biggest foe was despair, both for her and for me. She fought that one, too. And beat the crap out of it.

While I slept, she fought. She fought for me to get proper treatment. She fought to stay by my side, knowing that my fear of hospitals and my claustrophobia would lead to a panic attack when I woke up intubated and tied to my bed. She fought for a private room, because it would be the only way that she could stay with me. She fought exhaustion and worry. She fought fear. She fought a dozen enemies, any one of which I probably would have run from. Ultimately, however, the biggest foe was despair, both for her and for me. She fought that one, too. And beat the crap out of it.

Memo to the Angel of Death: Do not mess with the Mexican mama. She will pull out a chancla and beat you back to Hell where you came from.

The weeks and months following my initial release from the hospital were hard for both of us. I lost weight every day, just as her dad was doing next door. Esther was watching both of the men in her life slowly disappear, and there was not much of anything she could do about it. She tried everything, but I just continued to waste away. It would be some four months before we sorted out the problem and addressed it, through another round of surgeries and scrapes with death.

During that time, Esther stayed home from work. She was not going to leave me home alone, even if it meant that “home” might be a refrigerator box under a bridge by the time the year was done. For weeks on end, we did little more than sit on the couch together, watching virtually every movie and program available on Netflix. (We were reduced to Lone Ranger reruns before I finally felt well enough to get back to work). This was hardly the romantic marriage we envisioned 25 years ago. (We spent our silver anniversary in ICU. I know how to show a girl a good time). If I had the energy to kiss her, I was doing well for the day. Instead, we just….sat there.

And it was enough.

It reminded me of how much I love this woman, and how valuable her presence is to me. After all of these years, we  can sit in a room together without a thing to do, and it is enough. I suspect this is the kind of love that few people are blessed enough to experience, and for that I am sorry. Because I was able to lose everything this year and still be wealthy. My wife loves me. She endured. She stayed.

can sit in a room together without a thing to do, and it is enough. I suspect this is the kind of love that few people are blessed enough to experience, and for that I am sorry. Because I was able to lose everything this year and still be wealthy. My wife loves me. She endured. She stayed.

And, as always, she healed me.

I thank God that I have her.

Tomorrow: My God

Mormon bishops are an oddity. They are often compared to parish priest or a local minister, but the analogy falls apart quickly. Mormon bishops are not professional clergy. The do not apply for their position to preside over a congregation, and unless someone is completely out of his mind, they don’t campaign for it. They balance the demands of their callings with their own jobs or careers and family. They receive minimal and mostly informal training for their position, which they will only hold for five years or so before moving on to some other responsibility. It is a position free of pay, and frequently free of thanks.

In exchange for their efforts, they get to listen to and counsel repenting members of the Church, enduring through a litany of sins and predicaments that they most likely would prefer to know nothing of. They attend leadership meetings, ward councils, committees, and a parade of other meetings that would drive lesser men to drink. And, when families face catastrophes, they step into the breach and help to put things back together.

The last thing I wanted to do this year was to place another burden on my bishop’s shoulders. Bishop Jason Parr has been dealing with his own tragedy, having lost a young son in a car accident recently. He had more than enough on his plate without worrying about the Ghios. But one night as I lay in the hospital, in walked Bishop Parr, with his ubiquitous smile.

I wish I remembered more of that visit, but I wasn’t operating on the same level of reality as other folks. But I do remember two aspects of the conversation. The first dealt with my own despondency, and the natural question of “Why does this stuff keep happening to me?” He smiled even more broadly as he completely dodged the question. “I usually refer those kinds of questions to you or your blog.” Thanks a lot. But it was his gentle way of reminding me that I already knew the answer (or lack thereof) to that question and needed to point my mental faculties in a different direction. Jason and I have been friends for a lot of years, and he can get away with that kind of thing.

My second concern was more direct. “Jason, my family’s going to be in real trouble here.” His smile dropped for just a moment, then returned. “No, you’re not.” He assured me. He told me that people already were lining up to help us, including an online funding effort. He made himself very clear: My family would be taken care of, and there was no expiration date for that help.

It’s humbling to take help from anyone, but particularly from the Church. I’ve only had to do this once before (after my auto accident), and I did not like it. So I immediately started talking about how soon I could get back to work. The bishop would hear none of it. He told me, in so many words, to shut up and get better.

Somehow the bishop knew better than we did how bad things actually would get. I had plenty of false starts and false hopes over the months, with various financial mirages appearing, only to dissolve in the face of one more diagnosis or procedure. I tried to give Bishop Parr a cutoff date for help, but he stopped me. “I don’t want you doing anything to slow your recover because you are worried about finances. So what we’re going to do is this: I’ll tell you when you don’t need help any more.” Within days of that conversation, more bad new hit on the health front, and I would have been absolutely despondent had it not been for Bishop Parr’s prophetic promise.

And it wasn’t just financial help, although that relieved me from some of the most serious worry. There were the brief interviews in his office, as he checked on my progress and listened to my frustrations. He didn’t make me suffer through feel-good platitudes or empty promises. He was comforting, but realistic. I think that his own experience with tragedy make him a better comforter. He knows that there are some things that you just have to wait your way through, and there is no magic salve to make it feel better.

I’ve drawn heavily from Bishop Parr’s example of endurance and his unyielding faith. I don’t know that I can measure up to it, nor could I ever help him to the extent that he has helped my family. But I do know that in his dealings with me, he has demonstrated a Christ-like compassion and the mantle of priesthood power and authority. I trust him because I know he trusts God. I listen to him because I know he listens to God. And I am grateful that in this time of hardship for me and mine, the mantle of the bishopric has been his faithful shoulders.

Tomorrow: My Wife

Three of the people to whom I owe a great deal of debt aren’t here to receive my thanks. But one thing I have learned about suffering through a hardship is that it is helpful beyond measure to reflect on examples of those who have endured hardships well. In my case, three people come to mind as my examples of how to hold up under pressure and to endure with dignity. So many times in the past year I have not known what to do under my circumstances, so instead I just tried to do what I thought they would have done.

Mike Jacques

I’ve written about Mike Jacques before. Or at least I think I have. Brain damage does funny things to your memory, and laziness prohibits me from looking it up. No worries, Mike would laugh it off.

Mike was one of my dear friends years ago. He was one of the smartest and most interesting people I knew. A Vietnam-era veteran who had been exposed to Agent Orange, he was recovering from his first round of leukemia when I met him. His long hair, which he let grow in defiance of treatments that had taken his hair previously, certainly stood out in church, as did his passion for the Russian language. Mike and I had long conversations together, although they usually involved him talking and me listening. But those conversations entertained me to no end, and the family knew that if Brother Jacques called during dinner time, they should go ahead and eat without me. It was going to be a while.

Mike had a mantra that he followed during his first (successful) bout with leukemia, and his second (fatal) bout with it years later. He had moved out of state by the time his illness recurred, and I remember talking to him on the phone a month or two before his death. I asked him how he felt. He told me that everything hurt, and then he invoked his mantra: “But that’s ok. If it hurts, I’m still alive.”

I spoke those words out loud many times over the last nine months. And when I was in too much of an extremity to invoke them myself, my wife would recite them for me. That has been my standard for success this year. As long as it was still hurting, I was still in the game.

Thanks, Mike, for managing my expectations.

Frank Clementino

One of my favorite people ever was Frank Clementino. I met him near the end of his life, when heart and lung problems already had confined him to a wheelchair. Born in Italy (which automatically made him all right in my book), Frank was another bright man, and he possessed a powerful testimony of the gospel of Jesus Christ. His loving spirit and irrepressible sense of humor made you wonder sometimes if he realized he was sick.

But he knew. I learned early on from his wife that each Sunday, he faced a choice: He could take his pain medication and stay at home, unable to function, or he could skip the pain medications, endure the pain, and go to church. If Frank’s wheelchair was not in its familiar place on the right side of the chapel on Sunday, that meant that his pain was too much for him to bear. This went on for years before his death. To this day I miss seeing him there, showing us all what it really meant to “man up.”

Shortly after I had returned home from the hospital, the opportunity came to go to church for the fast and testimony meeting. If I recall correctly, this would have been in May, the first month after my return home. By that time, I had managed to progress beyond a walker to a cane, and although I couldn’t walk well, I at least could walk. Sort of. It was really more of an extended fall. But I wanted to be at church in order to bear my testimony and express my appreciation to the members of my ward. Esther told me I was crazy. I was too weak and in too much pain to leave the friendly confines of my living room. I remember lying in bed, weighing my options. Finally, I sat up at the side of the bed, and Esther asked me what I had decided. I told her that I decided that Frank would go. So I would.

There have been many times since then that I have hovered at the border of feeling well enough to go to church, but preferring not to. Every time I have invoked Frank’s name (sometimes grumbling at his determination and taking his name in vain) and sallied forth if I could. There were plenty of times that I just couldn’t, but if there was a question, I did it Frank’s way.

Thank you, Frank, for showing me how to fight.

Eloy Torres

My father in law was known more commonly as “Kaqui,” a nickname imposed on him for no good reason by my oldest daughter. Like most bad nicknames, it stuck.

In 1994, Eloy was diagnosed with prostate cancer. It was the beginning of a 21-year cancer marathon. Long before I took on three semi trucks and then a liquefied pancreas, Eloy was the original Man Who Could Not Die. He fought against cancer like a lion tamer, holding little more than a chair and a whip in the face of a monster. His will to live, and to stay by the side of his granddaughters, was beyond impressive. He would try any treatment and endure any indignity if it meant a chance to stay a bit longer.

Until he couldn’t. As is the way with cancer, it persists patiently until it wins. After two decades, it spread to his bones and then his lungs. In his final days, tumors were attacking virtually every bone in his body.

Coincidentally, his last fight was being conducted over the summer of this year, when my condition still seemed to be spinning out of control. Although he lived next door to us, walking to our house was a painful fifteen minute endurance contest for Kaqui, but he made it at least twice a day. To check on me. It was so humbling. He would stagger through the back door, ask how I was, give me a hug, and then collapse in my recliner for a two-hour nap.

I spent a lot of time looking at Kaqui this summer and thinking about his life. He had been a hard man in his youth, and not a great father to his daughter. But the diagnosis of cancer changed him fundamentally. Where others might have become bitter and hopeless, he softened and became a source of joy and hope for other people. He embraced the gospel and demonstrated a remarkable capacity for faith and service. He often laughed at his own infirmities, and he patiently accepted help when he had to.

Eloy taught me that you have a choice in the face of adversity. You can become calloused or compassionate. You can harden your heart or soften your soul. You can hate or love.

Eloy did it right. He found new meaning in life once it was threatened, and his hardships became the source of a quiet strength. He enriched lives even as his slipped away. Eloy finally succumbed to cancer this summer. I was there to hold his hand as he drew his last breath. In dying, he taught me how to live and how to endure. I don’t know that I ever can soften to the extent he did. I don’t know that I have the same capacity for compassion and hopefulness. But I know that I would certainly like to.

Thank you, Kaqui, for teaching me everything.

Tomorrow: My Bishop

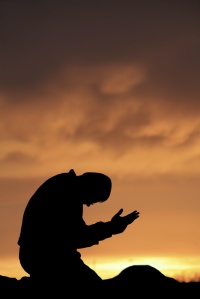

Living in Texas means that when your neighbor says, “You’re in my prayers,” they mean that they actually are offering prayers on your behalf. It isn’t a supportive figure of speech or a shorthand for “good thoughts.” Instead, it is a promise to exercise one’s faith on your behalf. And even if they haven’t told you they will pray for you, they often do.

I already had seen this when we had our car accident in 2012. Months later, people I never had met before would learn that my family was the one involved in the wreck, and they would tell me that when they drove by the accident, or saw reports of it on the news, “I prayed for you.” It was always said with sincerity, and I would feel the warm assurance that not only had the prayers been said, but they had been honored.

This time was no different. In my extremity, the community of believers rallied around my family with their prayers. And not just the Mormons. Once again, I heard from Baptists and evangelicals, people whose ministers believe that my Mormonism is hopelessly misguided, that they had called upon the power of God to heal me. Some of those prayers were individual, others made my congregations. A Muslim family with whom we are close let me know that not once, but several times, their mosque had prayed on my behalf. And the Mormons were there as well, praying for me and with me. Submitting my name to the prayer rolls of our temples. Remembering our family in congregational prayers.

This time was no different. In my extremity, the community of believers rallied around my family with their prayers. And not just the Mormons. Once again, I heard from Baptists and evangelicals, people whose ministers believe that my Mormonism is hopelessly misguided, that they had called upon the power of God to heal me. Some of those prayers were individual, others made my congregations. A Muslim family with whom we are close let me know that not once, but several times, their mosque had prayed on my behalf. And the Mormons were there as well, praying for me and with me. Submitting my name to the prayer rolls of our temples. Remembering our family in congregational prayers.

I love those who petitioned God on our behalf, and I am grateful for every prayer offered. I believe that our Father in Heaven listens to all of our prayers, and that they make a difference. Whether the prayer is made to Jesus, to Heavenly Father, or to Allah, there is a palpable power in it. In times of tragedy, it is refreshing to see details of doctrine set aside so that the community of the faithful, the broader family of believers, can join together in a common expression of brotherly love and trust in the divine.

I cannot adequately express the effect those prayers have had on me and my family. Nor can I explain why we were rescued when other good people–better people–are not. I have felt considerable guilt over the last several months as I have seen better men than me pass to the other side with what were less serious conditions. I have no idea why I am still here and people like Fred Brown and James Ojo are not.

But I am. And I know that miracles have attended my family once again. I should not be alive, but I am. The stress of  illness and financial difficulty should have torn my wife and I apart, but it did not. The mere fact that each morning I can wake up and reach out and take Esther’s hand is a wondrous miracle, and I attribute it to the collective prayers of the community of faith.

illness and financial difficulty should have torn my wife and I apart, but it did not. The mere fact that each morning I can wake up and reach out and take Esther’s hand is a wondrous miracle, and I attribute it to the collective prayers of the community of faith.

These experiences have transformed me in other ways. My defense of people of other faiths is more robust as a result of these nine months. While others engage in broad-brush criticism and condemnation of Islam, I cannot speak ill of those who have prayed for my family. Doctrinal differences with other Christians are a fair subject of discussion, but when someone has exercised his faith for me, I couldn’t care less that his view of the Trinity is different from mine.

It also has changed my own behavior with respect to prayers for others. I am very careful about saying that someone will be in my prayers unless I intend to make good on that promise. Often, I will stop what I am doing in that moment to say a prayer, so that my promise immediately is fulfilled. Other times I will jot the person’s name on an index card or make a note on my iPhone so that I can review it at the end of the day before saying my prayers.

What I have learned from doing this is that those prayers have an impact on me, regardless of what they do for the other person. Those for whom I pray stay on my mind, closer to the forefront of my concerns. I am more likely to follow up with the person to check on their status or perform some small act of service for them. I think that one of the ways that prayers are answered is not through divine intervention, but from stirring up Godlike love in the person who prays. We often become the answers to our own prayers. Not infrequently, our plea for the intervention of angels can transform us into ministering angels ourselves.

What I have learned from doing this is that those prayers have an impact on me, regardless of what they do for the other person. Those for whom I pray stay on my mind, closer to the forefront of my concerns. I am more likely to follow up with the person to check on their status or perform some small act of service for them. I think that one of the ways that prayers are answered is not through divine intervention, but from stirring up Godlike love in the person who prays. We often become the answers to our own prayers. Not infrequently, our plea for the intervention of angels can transform us into ministering angels ourselves.

I am deeply grateful for every prayer sent Heavenwards for me and my family. I love everyone who has remembered us in this way, and I respect and honor your faith. And I, in turn, pray for your welfare and happiness, especially during this holiday season. I do not know all of your names. In fact, I do not know most of your names. But regardless of whether I can put a face to your faith, you have knit my heart to yours.

Tomorrow: The Examples for Enduring Well

Fred Rogers once said that when tragedy strikes, you should look for the helpers. Some of those helpers are easy to find, and I have written about many of them already. It isn’t hard to remember the paramedics, the doctors, the nurses, and the family members. But when you go through an extended illness, with multiple invasive procedures and treatments, and you spend most of a month flat on your back, there are a thousand little things that can or need to be done to make the experience more tolerable.

So I want to thank the helpers.

They seemed to come out of the woodwork, and there were too many for me to mention all of them. In many cases, they dealt with needs at a time when I was unconscious or so compromised by pharmaceuticals that I had no idea what they were doing on my behalf. But I can give you at least a representative sample:

God bless the helpers.

Tomorrow: The Community of Faith

I’m chalking this up to (1) being in a coma when the events happened; (2) being stoned when I heard about it; and (3) I screw things up.

I wrote last night about a blessing giving to me at the beginning of my coma. I mistakenly put Tony Brigmon into that story. He was kind enough to point out to me that, while he did administer to me later, when he got to the hospital that day, I already had received a blessing, from Carlos Munoz and Vance Roper.

Didn’t mean to write Vance out of the story. Everything I said about my other priesthood-holding friends is true of him as well. He has been my friend for almost a quarter century, and during that time whenever our family has asked anything of him, he has been there. He’s the kind of guy who will give you the shirt off of his back, and then give you his back, too. He has been called in over many a late night to help me administer to my family, and I have been summoned many times under similar circumstances.

Didn’t mean to give you short-shrift, buddy. Thank you for being there for me.

I recall, years ago, being asked to go with a friend in a response to a call for a priesthood blessing. The adult son of a member of our ward had been involved in an accident at home and had suffered extensive third-degree burns. We were asked to “administer” to him, which in Mormon parlance means that two priesthood holders anoint him with consecrated oil and, in the name of Christ, lay their hands on his head and pronounce a blessing as moved upon by the Spirit. Usually one person anoints, and the other person gives voice for the blessing.

I recall, years ago, being asked to go with a friend in a response to a call for a priesthood blessing. The adult son of a member of our ward had been involved in an accident at home and had suffered extensive third-degree burns. We were asked to “administer” to him, which in Mormon parlance means that two priesthood holders anoint him with consecrated oil and, in the name of Christ, lay their hands on his head and pronounce a blessing as moved upon by the Spirit. Usually one person anoints, and the other person gives voice for the blessing.

I don’t know about anyone else, but when the circumstances are serious, I would rather do just about anything than be the person giving the blessing. Although no one pretends that they are speaking as dictated to by God, you still don’t want to say something stupid. You don’t want to announce that a person is going to be healed, and then they die. Nor do you want to destroy hope through a pessimistic blessing, only to have the person dance out of the hospital a day later. You do your best to follow the promptings of the Spirit, but my first prompting usually is: “Let the other guy do it.”

On that occasion, we asked the family who they wanted to do what. I started edging backwards and avoiding eye contact. They asked me to give the blessing anyway. Great. I really liked the guy, so I wanted to bless him that he would be fine. On the other hand, those burns were really impressive. Maybe I should just slur my words so no one knows what I said and hightail it out of there. (A similar strategy helped on the Bar exam. When I came to a question I wasn’t sure about, I fell back on the “write sloppy” approach. Worked just fine).

Decorum won out over panic, so I stayed and gave the blessing. I have no recollection at all what I said, but it must have been hopeful, because there were no dirty looks afterwards. And the guy did, in fact, completely recover. I am thankful that the Spirit showed up and took the situation over before Robin blew it completely.

So I can’t imagine what was going through the heads of two of my dearest friends when they were called to Parkland to administer to me. Both of them had been through this fairly recently with me, when my subcompact car was further subcompacted in a collision with three semi trucks. But things were a little less scary then. I was a bloody mess, but I was out of the woods relatively early: Broken, but not dying.

This time, as one of these good friends told me later, “It really looked like you weren’t going to make it.” He already had a pretty good history of giving blessings to people and having them die later. I have teased him about it unmercifully. When Tony Brigmon walks through the door to give you a blessing, call your lawyer quick to make sure your affairs are in order. I’m sure he thought there was a very good chance that this would be the last blessing I ever got.

My closest friend, Carlos Munoz, also was there. Back when I was in my car accident, he had made it to the hospital before the ambulance did. That’s just how he rolls. Master of Time and Space, and Servant to No Speed Limit. He had more on his mind than just the blessing. I was on a gurney in my new suit, and Esther asked him to help her take my pants off. “If I let them cut his new suit, he’s going to kill me,” she said. “If he wakes up and finds me taking off his pants, he is going to do worse to me,” he responded. Priorities, people.

This wasn’t going to be my last blessing. There were going to be several more in the coming months, as fears and physical problems would continue to mount. I would feel the hands of the people I respect most in the world resting on my head as my friends and brethren would exercise their faith on my behalf. And it would not end there. They were there to administer to my wife and children, providing sustaining strength to them as they suffered much more than I.

My family believes in priesthood blessings. They have been a source of divine aid and miraculous recovery many times in my family. I never felt closer to the Lord than when my father gave me a blessing. My daughters will wake me up at two in the morning to ask me to administer to them. We take seriously the power of prayers of faith, especially when exercised in the context of a priesthood blessing.

(I learned just this week that a circle of faithful female friends also stood around my bed and prayed at one point. Although women in our church do not “hold” the priesthood, their faith certainly works through the priesthood in a similar way. The priesthood is God’s power exercised on earth, and whether invoked through a priesthood blessing or through a prayer of faith, God responds in the same way. I wish that I could have been awake for that prayer. I know those women. You will not find greater faith anywhere).

One of the things I like about being a Mormon is that when we are in harm’s way, we don’t call upon a minister or pastor and hope that he will have the time to come and pray on our behalf. In the LDS Church, the priesthood is held by all worthy male adults. When trials or tragedies arise, you can call upon your own father (or, in this case, his substitute in my life, James Bratton), your brother, your adopted brothers, your home teachers, or your friends.

We often say that because the priesthood is the same, it doesn’t matter who blesses you, whether it is the President of the Church or a Primary teacher. But, to me, it makes all the difference who is there. When I was seriously ill at 12 years of age with the swine flu, I didn’t want President Kimball to administer to me. I wanted Dad. If I had been asked who I wanted there while I was in a coma, the list would have included Tony and Carlos. These are men who know me, and are among the closest friends I have had in life. I know their hearts. I trust them in a way that I would not trust a local minister whose ministry was his livelihood.

The hands on my head were familiar ones. I have seen them lift and bless other people. I have seen them work for the benefit of the less fortunate. I have seen them clasped with the hands of those they love. I know the works of those hands, and while anyone can use the priesthood on my behalf, the familiarity of those hands fortifies my faith and shortens the distance between me and the Master.

For all of those good brethren who have exercised their faith on my behalf this year, I thank you for your devotion and worthy efforts to do what is right. I thank you for the love that has called you out at all hours of the day and night. I thank you for the patience to listen to a broken man, reduced to tears, who needed to lean on your shoulders, because mine had lost all strength.

Thank you for invoking the powers of heaven for me and my family, and for standing as bulwarks between us and despair.

Tomorrow: The Helpers

These thoughts came to me as I sat in a very empty funeral home next to the body of a friend, as I pondered why we stand watch over the departed.

No comfort gives the pillow soft

You place beneath my head.

To ease your fears

And dry your tears

You primp and dress the dead.

Not in silks nor finest clothing

Need my body be adorned

All that I ask,

One simple task:

Do not send me off alone.

My body takes its resting place

By my spirit still will roam

And though I know

To whence I go

Please don’t send me off alone.

This one last time, your presence share

As I flee my useless bones

Though I cannot hear

I’ll know you’re near

And did not send me off alone.

With me you cannot travel

Nay, tonight I’ll walk alone

But for today

An hour stay

And with peace I’ll travel home.